It’s the biggest threat the U.S. power structure has faced in many years—a Black-led, multiracial wave of protests, uprisings, and strikes against the police and white supremacy in cities across the country. Defenders of the established order have responded with a variety of countermeasures, including direct police repression, vigilante violence, and propaganda campaigns designed to demonize, divide, and weaken the movement.

Another countermeasure that’s received less attention is cooptation—not just immediate, small-scale tactics such as mayors proclaiming Black Lives Matter or cops taking a knee, but large-scale strategic efforts to channel mass rage into limited changes that leave existing systems of power, hierarchy, and oppression fundamentally intact. This kind of cooptation isn’t coming from the White House and may be beyond the capacity of the Democratic Party leadership, but it is a force we need to contend with. Because as popular pressure increasingly exposes weaknesses in the current systems of social and political control, it creates openings for a resurgence of ruling-class liberalism and the cooptation strategies it has promoted for generations.

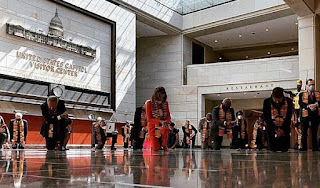

|

| Members of Congress kneel for Black Lives Matter |

The U.S. ruling class has leaned right for so long, it’s easy to forget that this stance isn’t inherent—or permanent. In the 1930s and again in the 1960s, during times of deep social crisis and large-scale radical mobilizations, capitalists sanctioned dramatic changes in the system of rule to preserve their own power. The business community abandoned New Deal liberalism starting in the late 1970s, partly for economic and geostrategic reasons and partly in response to grassroots-based right-wing backlash. But to assume that capitalists are automatically committed to neoliberalism or right-wing authoritarianism is to take a dangerously narrow view of ruling-class politics.

To put this situation in perspective, it’s helpful to look at how the U.S. ruling class responded to the African American urban uprisings of the 1960s. An excellent way to do that is by revisiting the book Black Awakening in Capitalist America: An Analytic History by journalist-turned-academic Robert L. Allen.

First published in 1969, Black Awakening is important for a number of reasons. For one, it’s a keen exposé of contradictions and tensions within the Black Power and Black nationalist movements of the late 1960s. For another, it’s a pioneering analysis of U.S. racial oppression as a system of domestic colonialism. Anticipating part of Butch Lee and Red Rover’s Night-Vision by over 20 years, Allen argued that “black America is now being transformed from a colonial nation into a neocolonial nation; a nation nonetheless subject to the will and domination of white America.” Under colonialism, state power had been fully in the hands of whites, but with neocolonialism African Americans were granted a significant degree of political power yet remained subordinated through various “indirect and subtle” means (14).

A third reason that Black Awakening is important, and the one I’m most concerned with here, is that it includes an invaluable discussion of ruling-class responses in the face of mass upheaval. In the broadest terms, Allen argued that

“In the United States today a program of domestic neocolonialism is rapidly advancing. It was designed to counter the potentially revolutionary thrust of the recent black rebellions in major cities across the country. This program was formulated by America’s corporate elite—the major owners, managers, and directors of the giant corporations, banks, and foundations which increasingly dominate the economy and society as a whole—because they believe that the urban revolts pose a serious threat to economic and political stability. Led by such organizations as the Ford Foundation, the Urban Coalition, and National Alliance of Businessmen, the corporatists are attempting with considerable success to co-opt the black power movement” (17).

Allen saw this program as emerging in the context of “several interlocked responses” to the rebellions from different sectors of the white power structure:

On the one hand there was the orthodox liberal who prescribed more New Deal welfarism as an antidote to the riots… [Another was] the shrill voices emanating from the embattled metropolises–voices demanding more policemen, more troops, more weapons, heavier armor, and tougher laws…. But between these two camps, there has arisen a third force: the corporate capitalist, the American businessman. He is interested in maintaining law and order, but he knows that there is little or nothing to gain and a great deal to lose in committing genocide against the blacks. His deeper interest is in reorganizing the ghetto ‘infrastructure,’ in creating a ghetto buffer class clearly committed to the dominant American institutions and values on the one hand, and on the other, in rejuvenating the black working class and integrating it into the American economy. Both are necessary if the city is to be salvaged and capitalism preserved” (194).

|

| McGeorge Bundy with President Lyndon Johnson, 1967 |

One of the architects of the neocolonialism program, who receives special attention in Allen’s study, was McGeorge Bundy. Child of an elite Boston family, Bundy spent five years as national security advisor to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, then left in 1966 to become president of the Ford Foundation. With this job change, Bundy shifted from a leading role in designing U.S. political-military operations in Vietnam to a leading role in designing establishment responses to the Black Liberation Movement.

Bundy quickly set a new tone as Ford Foundation president. In August 1966 he told the National Urban League’s annual banquet, “We believe that full equality for all American Negroes is now the most urgent domestic concern of this country. We believe that the Ford Foundation must play its full part in this field because it is dedicated by its charter to human welfare.” With Bundy as its head, the foundation broadened its grant-giving from relatively tame civil rights organizations such as the NAACP and Urban League to the more militant Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Allen explains that CORE appealed to the Ford Foundation because it talked about revolution but offered an “ambiguous and reformist definition of black power as simply black control of black communities,” fortified by increases in government and private aid. “From the Foundation’s point of view, old-style moderate leaders no longer exercised any real control [in the ghettos], while genuine black radicals were too dangerous” (146-47). In Cleveland, Ford financed a CORE-led voter registration and voter education campaign, which in November 1967 helped Carl Stokes win election as the first Black mayor of a major U.S. city.

Bundy recognized that repression and cooptation work best as two sides of the same coin. In a 1967 Foreign Affairs article titled “The End of Either/Or,” he wrote,

“with John F. Kennedy we enter a new age. Over and over he insisted on the double assertion of policies which stood in surface contradiction with each other: resistance to tyranny and relentless pursuit of accommodation; reinforcement of defense and new leadership for disarmament; counter-insurgency and the Peace Corps;… an Alliance for Progress and unremitting opposition to Castro; in sum, the olive branch and the arrows” (quoted 77).

Bundy’s approach meshed closely with the two-pronged national policy for dealing with urban revolts which, in Allen’s account, “evolved out of a series of studies and meetings held in 1967 at top government levels” (208). One prong was military containment: “make a massive show of force while minimizing the actual use of force” (208) by deploying large numbers of troops and riot police instructed to hold their fire but use tear gas and arrests extensively. The point was to keep things under control

“but not bear down with an iron fist, because this would further alienate an already greatly dissatisfied and volatile group. Furthermore, containment of the riots would buy time for the second prong of the new policy to take effect: an intensive program to convince black people that they as a group have a stake in the American system” (209).

In Allen’s view, the modulated military response did not point to a relaxation of repression. On the contrary, he predicted “a steady, although gradual increase in the level of repression.” Writing two years before activists made public the FBI’s Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO), Allen

“expected that one of the favorite tactics of police forces will be more frequently employed–namely, decapitation of militant groups and movements…. More and more militant leaders (white as well as black) are likely to be arrested on charges of conspiring to bomb, assassinate, and otherwise engage in illegal activity, even where there is very little evidence to substantiate these charges” (209 note 6).

The second, cooptive prong of the national policy involved extensive investments in Black-owned businesses by the Ford Foundation and others, collaborative government-business initiatives to train members of the “hardcore unemployed” and help them find jobs, and—above all—programs designed to foster a class of Black capitalists and managers.

“The theory was that such a class would ease ghetto tensions by providing living proof to black dissidents that they can assimilate into the system if only they discipline themselves and work at it tirelessly. A black capitalist class would serve thereby as a means of social control by disseminating the ideology and values of the dominant white society throughout the alienated ghetto masses” (212).

Another leading force in this effort was the National Urban Coalition, which was formed in August 1967 by business, labor, religious, civil rights, and government leaders, among them such major corporate executives as David Rockefeller and Henry Ford II. As an example of its work, the NUC’s New York branch, whose board of directors included Roy Innis of CORE, provided nascent inner-city businesses with both advice and venture capital, in a program that Allen described as “a sophisticated mechanism for selecting and aiding persons in the black community who are to be programmed into the class of black capitalists” (220). The program’s “use of semiautonomous development corporations avoids the stigma of white interference and allows for maximum financial maneuverability” while offering “the attractive promise of community participation” (221).

As Allen noted, this strategy to foster Black capitalism and give African Americans a bigger stake in the established order was “fraught with difficulties and contradictions” (245), not least the fact that it was expensive and thus vulnerable to an economic downturn. Indeed, partly as a result of the mid-1970s recession, by the late 70s business leaders had begun turning to the right and largely abandoned programs to reintegrate poor and working-class African Americans. However, they continued developing a Black capitalist class through other methods. Today’s U.S. ruling class is still white dominated and still upholds a system of racial oppression, but it includes a significantly greater sprinkling of Black and Brown faces than it did fifty years ago, and it has embraced an ideology of multicultural “inclusion” in its leading institutions far beyond what McGeorge Bundy promoted.

This change in complexion and ideology has influenced ruling class responses to more recent Black-led upsurges. Since George Floyd’s murder, U.S. companies have donated hundreds of millions of dollars to civil rights organizations. And while there is wide variation in how capitalists and their representatives talk about race, the liberal wing of the ruling class has gotten much more sophisticated than it was in past generations at incorporating elements of anti-racist discourse, including calls for structural change. For example, Foreign Affairs, journal of the Council on Foreign Relations and the same organ that published Bundy’s “The End of Either/Or” more than half a century ago, recently published an article by Chris Murphy, U.S. senator from Connecticut, expressing the hope that

“maybe the country is at the dawn of a second civil rights movement that will prompt fundamental reforms to its systems of law enforcement, criminal justice, housing, and school finance. Could it also be that Americans’ ability to squarely confront their demons and use the tools of democracy to profoundly alter the status quo will relight the country’s torch in the eyes of the world?”

The Ford Foundation, building on McGeorge Bundy’s legacy of outreach to militant civil right organizations, pledged four years ago to provide “long term support” to the Movement for Black Lives, declaring

“now is the time to stand by and amplify movements rooted in love, compassion, and dignity for all people. Now is the time to call for an end to state violence directed at communities of color. And now is the time to advocate for investment in public services—including but not limited to police reform—together with education, health, and employment in communities and for people that have historically had less opportunity and access to all those things.”

New America, a liberal elite think tank that has taken a special interest in counterinsurgency strategy, has for several years been promoting calls for police reform, as in a 2017 panel discussion titled “Breaking the Chokehold: A Radical Approach to Disrupting the Policing System.” In response to the recent Black-led uprisings in Minneapolis and other cities following George Floyd’s killing, New America published an article that defended the protesters’ destruction of property as “a direct challenge to a system built on the exploitation and oppression of Black lives.” (The article was written by Malcom Glenn, a New America fellow, who had made national news in 2007 as the first African American president of Harvard’s student newspaper in over half a century.)

How ruling-class anti-racism will be translated into specific policy initiatives in the coming months and years remains to be seen, and depends partly on how the grassroots movement against white supremacy continues to unfold. If the experiences of the late 1960s are a guide, we can expect such cooptive initiatives to have a few characteristics:

- They will embrace the language of combating oppression in dramatic-sounding terms.

- They will threaten some (especially local) entrenched white interests and centers of privilege without calling overall systems of power into question.

- They will tend to divide the movement against white supremacy, by promoting or elevating some sections within communities of color, and by exacerbating tensions between radical and system-loyal forces.

- They will be promoted in tandem with political repression, both overt and covert.

In sounding these warnings, I’m not arguing that calls for incremental reforms are inherently bad. Reforms of the existing system can be valuable and important, if they substantively improve—or save—people’s lives. In this context it’s helpful to remember Robert Allen’s words on the difference between reforms and reformism:

“The general attack on reformism in this study is not meant to imply that there is no role for reforms in a revolutionary struggle. In a struggle to transform an oppressive society, it is indeed necessary to fight for certain reforms, but this requires that those who are oppressed are conscious (or made conscious) of how the reforms fit into an over-all strategy for social change. [F]requently reforms serve mainly to salvage and buttress a society which in its totality remains as exploitative as ever” (157 note 12).

Note:

All page number citations are from Robert L. Allen, Black Awakening in Capitalist America: An Analytic History (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1969).

Photos:

1. By Office of Congressman Colin Allred, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

2. By Yoichi Okamoto, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Here is a collection of links on repression & cooperation of Black movements in the u.s. over the last decade:

https://types.mataroa.blog/blog/m4bl-blm/