I can think of at least four reasons why leftists and antifascists need a good analysis of antisemitism:

- Antisemitism kills Jews. There should be no question about this after the Pittsburgh synagogue massacre. In the United States, Gentiles are not killing Jews on anywhere near the scale of cops killing Black people, or husbands and boyfriends killing women, or cisgender folks killing trans people, but anti-Jewish violence is real. And if the current political climate means anything, it is likely to get worse.

- Antisemitism drives far right politics. From the neonazis who call Jews the main enemy of the white race, to Patriot groups that stockpile weapons to confront “globalist elites,” to Christian theocrats who look forward to mass killings of Jews and mass conversion of the survivors, U.S. far rightists put antisemitic themes at the center of their belief systems. These forces have been closely bound up with Donald Trump’s political rise, and over the past two years they have helped blast away the taboo against antisemitism in U.S. political discourse.

- Antisemitism is a problem within the left. Conservatives have long portrayed the left—falsely—as the main source of Jew-hatred, but that doesn’t mean leftists have done a good job of combating it. Antisemites such as Gilad Atzmon and Kevin Barrett have been welcomed into respected radical venues such as CounterPunch and Left Forum, and efforts to correct this have had mixed success, often meeting fierce opposition and denial. Many radical Jews have encountered antisemitic attitudes in leftist circles, such as “Jews control the media” or “the Zionist lobby controls Congress.” Excusing antisemitism, let alone promoting it, hurts the left’s credibility and integrity and weakens all our efforts.

- The charge of antisemitism has been widely misused. Zionist groups often label criticisms of Israel or calls for Palestinian self-determination as inherently “antisemitic.” Such claims falsely equate Jews’ safety with Israel’s repressive and murderous policies, discredit principled efforts to combat antisemitism (whether by opponents or supporters of the Israeli state), and mask Zionism’s own long history of collusion with Jews’ oppression. Misuse of the antisemitism charge doesn’t cause or excuse anti-Jewish scapegoating, but it highlights the need for clear radical analysis.

My aim here is to help strengthen radical antifascist analysis of antisemitism by pulling together some of the best insights I’ve found in other people’s writings. I’m primarily concerned with far right antisemitism, because far rightists are spearheading the resurgence of scapegoating and violence against Jews in the United States and elsewhere. At the same time, it’s important to look at how far right antisemitism is rooted in U.S. political culture as a whole, and in the structural dynamics of Jews’ roles in U.S. society. In addition, it’s important to recognize that far right antisemitism can take sharply different ideological forms, resulting in different policies and with different implications for antifascist strategy.

There are a lot of good writings about antisemitism. In this post I will highlight four works that explore the topic in different ways and, in combination, address many of the key issues involved. All four are freely available online. Three of them were published in 2017, against the backdrop of Trump’s election and the far right upsurge that contributed to it, while the fourth was published in 2009, abut a year after Barack Obama took office, a time when U.S. far rightists of various kinds were mustering their forces. Here are the four:

- Eric K. Ward, “Skin in the Game: How Antisemitism Animates White Nationalism”

- Jews for Racial & Economic Justice, Understanding Antisemitism: An Offering to Our Movement

- Ben Lorber, “Understanding Alt-Right Antisemitism”

- Rachel Tabachnick, “The New Christian Zionism and the Jews: A Love/Hate Relationship”

“The driving force of white dispossession”

I want to start with Eric K. Ward’s “Skin in the Game: How Antisemitism Animates White Nationalism,” because it lays out a case for why understanding and combating antisemitism should be a strategic priority. As Ward argues, the modern white nationalist movement sees Jews not just as one of its enemies, but as the main enemy—the group that’s chiefly responsible for most of what’s wrong with U.S. society today:

“The successes of the civil rights movement created a terrible problem for White supremacist ideology. White supremacism—inscribed de jure by the Jim Crow regime and upheld de facto outside the South—had been the law of the land, and a Black-led social movement had toppled the political regime that supported it. How could a race of inferiors have unseated this power structure through organizing alone? For that matter, how could feminists and LGBTQ people have upended traditional gender relations, leftists mounted a challenge to global capitalism, Muslims won billions of converts to Islam? How do you explain the boundary-crossing allure of hip hop? The election of a Black president? Some secret cabal, some mythological power, must be manipulating the social order behind the scenes. This diabolical evil must control television, banking, entertainment, education, and even Washington, D.C. It must be brainwashing White people, rendering them racially unconscious.

* * *“White supremacism through the collapse of Jim Crow was a conservative movement centered on a state-sanctioned anti-Blackness that sought to maintain a racist status quo. The White nationalist movement that evolved from it in the 1970s was a revolutionary movement that saw itself as the vanguard of a new, Whites-only state. This latter movement, then and now, positions Jews as the absolute other, the driving force of White dispossession—which means the other channels of its hatred cannot be intercepted without directly taking on antisemitism.”

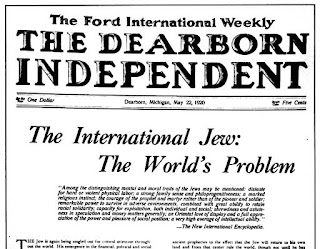

|

| Henry Ford’s antisemitic propaganda campaign, 1920s |

The Pittsburgh synagogue massacre offers an example of how antisemitism is bound up with other white nationalist themes. Shortly before taking his guns to Tree of Life, neonazi Robert Bowers denounced the Jewish refugee aid organization HIAS for bringing “invaders in that kill our people.” Here and elsewhere, white nationalists see Jews as the wirepullers directing other groups that threaten the white race.

Ward notes that white nationalism is a “fractious” movement that “does not take a single unified position on the Jewish question.” To elaborate on Ward’s point, some white nationalists think all Jews should be killed, while others think we wouldn’t be a threat if we all moved to Israel. And a few, such as Jared Taylor of American Renaissance, have even reached out to a few right-wing Jews to join them. Nevertheless, scapegoating Jews and Jewish power has been a “throughline” from David Duke’s remake of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1970s to the alt-right of today.

Much of “Skin in the Game” traces Ward’s political development as a “Black male punk” who grew up in southern California and moved to Oregon, and who “began to fight White nationalism because my world, my scene, my friends, and my music were under neonazi attack.” It was in this context that he came to identify antisemitism as “a particular and potent form of racism so central to White supremacy that Black people would not win our freedom without tearing it down.” Yet he also encountered resistance to addressing antisemitism from “the most established progressive antiracist leaders, organizations, coalitions, and foundations around the country.” These groups were committed to a simple model of racial oppression, in which Jews (or at least Ashkenazi Jews) were white and therefore talking about antisemitism would “deny the workings of White privilege.”

Ward’s solution to this dilemma is to call European American Jews’ white privilege into question. The argument here is ambiguous: at some points he refers to this privilege as a “myth” or a “fantasy,” which I think is at best oversimplified (because clearly we European American Jews do have access to white privilege at least most of the time), but elsewhere he refers to it as “provisional,” which hints at a more complex analysis.

The most accessible targets for popular anger

Some of that analysis can be found in my second recommended work: the pamphlet Understanding Antisemitism: An Offering to Our Movement, produced by Jews for Racial & Economic Justice. JFREJ argues that Jews

“suffer from ‘definitional instability’ when it comes to race…. Like the Irish and Italians, light-skinned Jews of European descent once faced pervasive, racialized bigotry. Today they primarily identify as white and are read as white, benefit from white privilege, and participate in upholding the system of white supremacy. However, this whiteness is contextual and conditional. …antisemitic beliefs predate modern white supremacy ideology. But white supremacy has since been incorporated into antisemitism, creating a shifting, slippery mixture of religious intolerance, mythology and racism. This means that Jews can sometimes be racialized as white, but antisemitism persists, and white Jews can still be considered ‘other’ because of religious difference and cultural stereotypes” (9).

I’ve argued elsewhere that American Jews’ racial “instability” falls into distinct historical periods: through most of U.S. history, Jews of European descent have been defined as white, but this was not the case from the 1880s to the 1940s, when millions of southern and eastern Europeans (including most Jews) “temporarily formed an intermediate group in the racial hierarchy, above people of color but below native-born whites. During this time, and none other, Jews in the U.S. faced a wave of systematic discrimination in jobs, schools, and housing, and anti-Jewish propaganda, organizing, and violence reached record levels.” During other periods, white privilege has mitigated the impact of antisemitism, but has never offered Jews full protection from scapegoating and violence.

JFREJ’s Understanding Antisemitism is notable in particular because it presents a structural model of antisemitism, in which Jews (a) become concentrated in highly visible positions of relative privilege, (b) are used as scapegoats to divert popular anger away from the real centers of power and oppression, and (c) experience alternating periods of relative acceptance and intense, violent persecution:

“Many oppressions, such as anti-Black racism in the United States, could be said to require a fixed hierarchy or binary values system…. By contrast, antisemitism is often described as ‘cyclical.’ The Jewish experience in Europe has been characterized as cycling between periods of Jewish stability and even success, only to be followed by periods of intense anti-Jewish sentiment and violence…. In order for [myths of Jewish power] to be plausible and gain purchase, Jews must accumulate at least some wealth and standing in society…. When the workers in these countries got angry about their exploitation, the most accessible targets were often Jews, rather than the elite political and economic actors who actually had power over the system and were almost exclusively Christian” (15).

This same dynamic, JFREJ argues, has been replicated in the modern United States, in a context of “racialized capitalist exploitation”:

“As they became classified as white, a large sector of assimilable Jews in the United States acquired real privileges such as a path into professional roles like teachers, social workers, doctors, or lawyers. They took on roles as intermediaries—middle agents—between large institutions and the people that they service. In big cities, these professionals are often the face of systemic racism and class oppression, delivered through schools, hospitals, government agencies, and financial institutions and service provision non-profits. Neither the professionals in middle-agent roles, or their poor, working class and POC clients are actually empowered to change the system. However, the professionals do have more positional power relative to their clients. For those clients, these doctors, lawyers, social workers and teachers—often Jewish—are the most immediately accessible face of those systems. They are the ‘middlemen’ between the oppressed and the systems oppressing them. This focuses anger about racism on Jews, and because of antisemitic stereotypes about Jews, that anger spreads and persists even in places where there are few, or no, Jews” (26, 28).

This structural model of antisemitism has been around for decades and is partly based on Belgian Trotskyist Abram Leon’s theory of Jews as a “people-class,” yet it is widely ignored by today’s U.S. left. Understanding Antisemitism presents it effectively while wisely cautioning against treating the cyclical dynamic as universal or permanent. As JFREJ notes, it doesn’t necessarily describe the history of Jewish-Gentile relations in North Africa or the Middle East, for example. I would extend the caveats further. In particular, I disagree with JFREJ’s claim that the Nazi genocide was a “clear example” of scapegoating Jews to redirect working-class rage away from the ruling class. If, as JFREJ quotes Aurora Levins Morales, “the goal [of antisemitism] is not to crush us, it’s to have us available for crushing” (17) then Nazism went completely off script, by making the systematic extermination of Jews an overriding goal that overrode all other political and military priorities. However, as a first approximation for understanding what generates and sustains antisemitism today, JFREJ’s approach is miles ahead of the conventional—and tautological—claim that antisemitism is simply an expression of “hate.”

Understanding Antisemitism has a lot more to offer, such as a good overview of Jews’ ethnic and economic diversity in the United States, a thoughtful discussion of how anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim oppressions are related, and a good argument for the strategic value of supporting the leadership of Jews of Color. The pamphlet also offers a useful starting discussion of Israel and Zionism, arguing on the one hand that it is legitimate to criticize Israel and Zionism as oppressive to Palestinians, and on the other hand that Israel’s oppressive policies are comparable to what many states practice around the world, and thus singling out Israel for special condemnation tends to play into antisemitism.

But the pamphlet has other shortcomings as well. Understanding Antisemitism includes no discussion of gender or the ways that antisemitism and male supremacy have interacted and reinforced each other. The pamphlet says nothing about Zionism’s long history of promoting antisemitic stereotypes and allying with antisemites in the name of building the Jewish state. And aside from a brief note in the Glossary, there is no discussion of the Christian right, although the United States has far more Christian rightists than white nationalists. This is consistent with the silence about Zionism’s support for antisemitism, since most Christian rightists are both pro-Zionist and antisemitic.

“Embedding themselves like a virus”

To begin to address these limitations, I turn to my third recommended work on the topic: Ben Lorber’s essay, “Understanding Alt-Right Antisemitism.” Lorber’s aim here is to examine “the ideology of antisemitism on the alt-right, and its intersection with alt-right Zionism, in comparison with anti-Jewish ideologies of the 20th century.” In the process, he elucidates some themes whose significance goes far beyond Richard Spencer and his comrades.

|

| Antifascist rally in Boston, 11/18/2017 |

Lorber’s analysis of alt-right antisemitism focuses largely on the work of Kevin MacDonald, a retired academic and one of white nationalism’s most influential theoreticians. MacDonald edits The Occidental Quarterly and its online counterpart, The Occidental Observer, and has published a series of books on Jews and Judaism. The basic premises found here and in the works of other alt-rightists are standard antisemitic fare going back to The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and earlier. As summarized by Lorber, “a tight-knit Jewish ‘ingroup’ embeds itself, like a virus, within the pores of [western societies], siphoning off resources, rising to the elite and disarming all defenses against their invasion.” This ingroup has worked stealthily to gain control of all the major power centers from Hollywood to the IMF, and has promoted civil rights, multiculturalism, feminism, and open immigration policies within the United States—while using neoliberal austerity policies to subjugate nation-states in Europe and elsewhere. In all these spheres, Jews function as the master puppeteers. “While other hated ethnic and religious groups, such as blacks, Latinos, Arabs and Muslims, represent external threats, Jews, [alt-rightists] claim, destabilize White European-American society from within, through the gradual, imperceptible institutionalization of creeping white genocide.”

In drawing parallels between the antisemitism of today’s alt-right and 20th-century fascist movements, Lorber draws on Moishe Postone’s brilliant essay “Anti-Semitism and National Socialism,” which elucidated modern antisemitism’s concept of Jewish power:

“‘What characterizes the power imputed to the Jews in modern anti-Semitism,’ writes Postone, ‘is that it is mysteriously intangible, abstract, and universal. It is considered to be a form of power that does not manifest itself directly, but must find another mode of expression. It seeks a concrete carrier, whether political, social, or cultural, through which it can work… It is considered to stand behind phenomena, but not to be identical with them. Its source is therefore deemed hidden—conspiratorial. The Jews represent an immensely powerful, intangible, international conspiracy.’”

Modern antisemitism, Postone explained further, set up a phony dichotomy between the “abstract” (rootless, cosmopolitan) power of “unproductive” finance capital and the “concrete” (rooted, patriotic) power of “productive” industrial capital (ignoring the reality that industrial and financial capital are integrally connected). Thus anger at capitalism could be channeled into hatred of Jews—the socialism of fools. At the same time, Jews’ abstract power was identified not only with the ruthless financier but also the dangerous leftist—two faces of the modern world, both of which threatened the traditional social order. Both Nazism in the 1930s and the alt-right today follow this same basic schema.

Along with these parallels, Lorber’s essay also points to certain distinctive features of alt-right antisemitism. One, which Lorber mentions only in passing, is the emphasis on evolutionary psychology. Although earlier generations of antisemites made use of social Darwinism and the image of a ruthless struggle between races, alt-rightists have updated this approach for the 21st century. MacDonald, an evolutionary psychologist by profession, has labeled Judaism a “group evolutionary strategy,” providing scapegoating and demonization with a modern-sounding, pseudo-scientific veneer. Looking beyond the scope of Lorber’s essay, evolutionary psychology has also strongly influenced alt-right gender theory, via the writings of various manosphere figures and male tribalist Jack Donovan (who was active in the alt-right for years before repudiating its white nationalism in the wake of the August 2017 “Unite the Right” rally).

Lorber devotes more attention to another distinctive feature of the alt-right: its admiration for Zionism. As he notes, “old-school” white nationalists such as David Duke have tended to demonize Israel and treat “Zionism” as a code-word for the international Jewish conspiracy. In contrast, many alt-right figures have endorsed the Zionist project as a positive step toward racial separation. “I do not oppose the existence of Israel,” Lorber quotes Counter-Currents editor Greg Johnson: “I oppose the Jewish diaspora in the United States and other white societies. I would like to see the white peoples of the world break the power of the Jewish diaspora and send the Jews to Israel, where they will have to learn how to be a normal nation.” Other alt-rightists, such as Richard Spencer, have written admiringly about Zionism as an example of ethnonationalism that white Americans and Europeans should emulate.

Lorber points out that there is a long history of antisemites supporting Zionism—such as Henry Ford in the 1920s—and that political Zionism’s founder Theodor Herzl proposed that his movement work with “respectable anti-Semites” who would support the removal of Jews from western societies. In the process, Herzl believed, “the anti-Semites will become our most dependable friends, the anti-Semitic countries our allies.” (The state of Israel later implemented Herzl’s vision when it cultivated friendly relations, for example, with antisemitic governments in South Africa and Argentina.)

By highlighting the compatibility of antisemitism and Zionism, Lorber’s essay fills one of the important gaps in JFREJ’s Understanding Antisemitism pamphlet. It also helps us understand the politics of Donald Trump, who offers aggressive support for Israel’s apartheid and settler-colonialism while also echoing and amplifying antisemitic conspiracy theories.

Fish to be caught

My fourth recommended text follows a related thread. Rachel Tabachnick’s essay “The New Christian Zionism and the Jews: A Love/Hate Relationship,” first published in late 2009, examines a form of right-wing antisemitism that often gets left out of the discussion. The Christian right, a mass movement that aims to impose a repressive, reactionary version of Christianity on U.S. society, is anti-Jewish by definition, but it’s rarely viewed that way because most Christian rightists are staunchly pro-Zionist.

|

| Christian right: In the End Times, all Jews will die or convert |

Tabachnick’s essay identifies both similarities and differences between Christian right antisemitism and its white nationalist counterpart. Christian rightists, and specifically Christian Zionists, promote standard antisemitic tropes, such as portraying Jews as preoccupied with money and claiming that Jewish bankers engage in sinister plots to weaken the U.S. economy. Christian Zionists also look forward to future mass killings of Jews as a key part of a divine plan. On a more basic level, Christian Zionists, like white nationalists, see Jews as exercising an influence over human affairs that is vastly out of proportion to our numbers or actual roles in society.

But there are also important contrasts between the Christian right’s religious antisemitism and white nationalists’ racial antisemitism. White nationalists believe that Jews are a race apart, intrinsically threaten whites, and must be either physically separated from whites or exterminated. But most Christian rightists claim, insidiously, to love Jews. They believe that Jewishness is a redeemable flaw, which can be overcome by accepting Jesus as humanity’s divine savior. Most of them believe, further, that as God’s original chosen people Jews have an important role to play in the End Times, and that Israel’s founding and growth are important steps toward Jesus’s return. “Christian Zionists,” Tabachnick notes, “talk about themselves as ‘fishers’ who entice Jews to move to Israel, while ‘hunters’ are those who violently force the Jews who are unresponsive to the fishers.” John Hagee, a prominent Christian Zionist leader, notoriously referred to Hitler as a hunter who was sent by God.

Tabachnick also describes a trend within Christian Zionism that is intensifying its anti-Jewish momentum:

“The traditional fundamentalist leaders of the movement preach that Jews returning to the Holy Land are a necessary part of the end times in which born-again Christians will escape death as they are raptured into heaven. Jews and other nonbelievers will remain on earth to suffer under the seven-year reign of the anti-Christ. Then, as the story goes, Jesus will come back with his armies, be accepted by the surviving Jews, and reign for a thousand years. This belief motivates adherents to send funds for West Bank settlements, to lobby for preemptive wars seen as precursors to the end times, and support Jews in the diaspora to make ‘aliyah’ and move to Israel.

“Now Christian Zionism – along with much of evangelicalism – is being swept by a charismatic movement which has rewritten the role of Jews in their end times narrative…. In their increasingly popular narrative, it is not unconverted but only converted or so-called Messianic Jews who will serve as the trigger for the return of Jesus and the advent of the millennial (thousand year) kingdom on earth. This growing belief is driving the movement to aggressively proselytize Jews and to support ‘Messianic’ ministries in both Israel and Jewish communities worldwide. One splinter group has even taken this story to an extreme, saying they themselves are the ‘true Israelites’ who will play the prophetic role of establishing heaven on earth by moving to Israel.”

This Christian right focus on “Messianic” Jews (those who have converted to Christianity but still retain Jewish identity and elements of Jewish ritual) is part of the context in which Mike Pence invited a “Messianic rabbi” to offer a public prayer for those killed in the Pittsburgh synagogue massacre.

The charismatic movement that Tabachnick refers to is called New Apostolic Reformation (NAR). Founded in 1996, NAR has over three million followers in the United States and many more worldwide, as well as an extensive network of ministries and media organs. It is one of the leading forces on the far right end of the Christian right spectrum, calling on Christians not just to ban abortion and same-sex marriage, but to “take dominion” over all spheres of society. As I wrote in Insurgent Supremacists,

“NAR combines a theocratic vision with an organizational structure that is far more centralized and authoritarian than most on the Christian right…. NAR leaders use ‘strategic-level’ spiritual warfare to cast out evil spirits that are supposedly ruling over whole cities, regions, or countries—or over whole groups of people, such as homosexuals or Muslims…. NAR leaders teach that their adherents will develop vast supernatural powers, such as defying gravity or healing every person inside a hospital just by laying hands on the building. Eventually, these people will become ‘manifest sons of God,’ who essentially have God-like powers over life and death. In the End Times, too, some one or two billion people will convert to Christianity, and God will transfer control of all wealth to the NAR apostles” (38-39).

NAR’s leaders have also enthusiastically supported Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy and administration.

Because of their political support for Israel, Christian Zionists have been warmly received by Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu and other members of his Likud Party, as well as leading American Jewish figures such as Anti-Defamation League head Abraham Foxman and the American Israel Public Affairs Committee. Yet as Tabachnick writes,

“Christian Zionists openly teach narratives that parallel the story lines of overt anti-Semitism in which Jews are portrayed not as ordinary people, but as superhuman or subhuman. With almost no challenge (and often endorsement) from Jewish leadership, Christian Zionists are stripping away the hard-won humanity of Jews with a broadcast capacity and international reach that overtly antisemitic organizations could never match.”

Each of the four essays I’ve profiled here offers important insights about far right antisemitism, and in combination they enable us to begin piecing together a fuller and more powerful analysis. Some of the themes I would emphasize in summary are:

- Antisemitism centers on a myth of Jewish power – a power that is superhuman, hidden, and dangerous. This mythical power often stands in for actual systems of oppression and exploitation.

- Antisemitism demonizes Jews and often seeks to expel or annihilate us, but it can also involve twisted forms of respect or admiration.

- Antisemitism plays a strategically pivotal role in the politics of multiple far right movements. White nationalists regard Jews as their principal enemy, while Christian Zionists regard Jews as a special community whose elimination is essential to God’s plan for the world.

- Far right antisemitism takes dramatically different forms, as embodied in the contrast between racial and religious ideologies, and in varying positions with regard to Zionism.

- Antisemitic scapegoating is historically rooted in structural dynamics that tend to concentrate Jews in prominent positions of relative privilege.

- Antisemitism in the United States is interwoven in complex ways with the system of white supremacy, and Jews are targeted in ways that differ from but are interconnected with the targeting of people of color.

The texts discussed here are just a few of many useful writings about antisemitism and its relationship with far right politics. Strengthening our understanding of these issues is a vital part of building a strong antifascist movement.

Photo credits:

1. Front page of The Dearborn Independent, Henry Ford’s newspaper, 22 May 1920 (public domain), via Wikimedia Commons.

2. Photo by Mark Nozell (CC BY 2.0), via Wikimedia Commons.

3. Photo by Julian Osley, Poster on the notice-board of Campsbourne Baptist Church and Centre, Hornsey High Street, London, N8, February 2010 (CC BY 2.0), via Wikimedia Commons.

Matthew, I’d like to raise a few questions about the following excerpt. I’m not sure whether it reflects your position or is a summary of Postone’s. I’m assuming it makes no difference to my argument but I could be wrong.

Modern antisemitism, Postone explained further, set up a phony dichotomy between the “abstract” (rootless, cosmopolitan) power of “unproductive” finance capital and the “concrete” (rooted, patriotic) power of “productive” industrial capital (ignoring the reality that industrial and financial capital are integrally connected).

One minor point: the ‘phony dichotomy’ that is referenced is a characteristic of a range of politics including many historic populisms and essentially all variants of productivist Marxism. While such politics often include antisemitism, anti-semitism doesn’t always play the central causative role that is implied by the language…“modern antisemitism…set up”.

My major questions center on the parenthetical phrase that I have highlighted and the ‘abstract’ versus ‘concrete’ power framing earlier in the passage. I doubt that many serious fascists are actually “…ignoring the reality…” of the connections between industrial and financial capitaI. (I could provide some citations if this is a contentious point; for example, the recent Little Rock speech of Matt Heimbach.) I’m also sure that most fascists see the various forms of debt peonage as a very concrete manifestation of finance capital – I do as well. In short, the issues involved in distinguishing between a revolutionary left and a radical (anti-Semitic) fascist critique of capitalism cannot be presented in such an axiomatic fashion. The differences must be clarified through an examination of the actual changing content of capitalism as a system. I would argue that such an investigation will quickly reveal the inadequacy of the “integrally connected” formulation of the relationship between financial and industrial capital that dates back a century to Lenin. At most it is a starting point for investigation. It does not answer the important contemporary questions about the relationship between financial and industrial capital and the ruling class fractions that are identified with each of them.

For revolutionaries on both the left and the right, there are important issues concerning the changing terms and content of the relationship between financial and industrial capital and its implications for political strategy. My own opinion is that by any reasonable metrics the global capitalist framework that has emerged over the past few decades has dramatically subordinated industrial capital to financial capital; and – what amounts to much the same thing – nationally-based capital to transnational capital. In this process, new relationships among ruling class elites and between these elites and various elements and institutions of state power are emerging. These result in decisive changes in the terms and character of class and popular struggles. I recognize the contradictory elements of the process, but think the general trajectory is evident and arguably, without rupturing the framework of capitalism, it is irreversible.

If I posit the accelerating process of transnational financialization and the emergence of a transnational ruling class out of it – a ruling class that is an essentially stateless, cosmopolitan global elite – I would hope the ensuing arguments would center on material facts and logical implications. However, I see a tendency in the current left to cast them as moral issues – where use of terms such as ‘globalist’ and ‘cosmopolitan’, even financialization, become evidence of an underlying anti-semitism that cripples further discussion …am I wrong?

Don Hamerquist

Don,

Thank you for these thoughtful questions and criticisms. I certainly agree that the formulations presented in this essay should not be treated as axiomatic, but rather as approximations intended to deepen understanding. There is plenty of room for improvement.

With regard to your “minor point,” I don’t see any conflict with Postone’s analysis or mine. Arguing that antisemitism draws a false dichotomy between industrial capital and finance capital doesn’t mean it’s the only viewpoint that does this. The Jacksonians in the 1830s were an example of a populist movement that railed against “the money power” without scapegoating Jews. I’ve never heard the term “productivist Marxism” before, so I can’t comment on that without knowing more. However, saying that antisemitism doesn’t necessarily cause this dichotomy isn’t quite enough. Because in the United States today, any time you are denouncing the power of bankers without critiquing capitalism as a system, you are — intentionally or unintentionally — offering claims that antisemites will likely celebrate and embrace.

On your main points: first, the article “Principal Enemy” is specifically about antisemitism, not about fascist politics as a whole. Setting aside the fact that not all forms of fascism have targeted Jews, other ideological threads besides antisemitism help to shape fascists’ relationship with capitalism, such as their positions on geopolitics, the structure of the state, political organization and strategy, and programmatic goals.

That said, I agree it’s an overgeneralization to say that current-day antisemitism (or fascist antisemitism more specifically) attacks “abstract” finance capital while defending “concrete” industrial capital, as Postone wrote about German Nazi ideology. Banker-bashing remains important, but antisemitism takes different forms and uses different forms of scapegoating, such as targeting “globalists” who threaten “national sovereignty” or denouncing a “universalism” that suppresses “biocultural diversity.” (Note that rejection of universalism, which is a major theme across both the alt-right and the European New Right, fits Postone’s larger theme of fetishizing concreteness over abstraction.) For Third Positionists, the Jewish enemy may even be identified with capitalists as a class, but Third Positionism has much less of an organized presence within the U.S. far right than it used to, as Matt Heimbach’s story illustrates (being expelled from the National Socialist Movement as a “communist” after helping to destroy his own Traditionalist Worker Party).

On the issue of some leftist arguments being mis-interpreted as antisemitic, I agree that we need to be able to discuss financialization or global/transnational capitalism without these topics automatically being seen as anti-Jewish. Given that such responses are out there on the left, I think it’s important to address the issue directly and point out the differences between a genuinely radical analysis and anti-Jewish scapegoating, such as delineating a class analysis from conspiracy theories.