In keeping with discussion and debate on A22 in PDX and its broader meanings for antifascism and developing a revolutionary liberatory vision, we post the following from Paul O’Banion in which, while making an assessment of that days organizing and actions, O’Banion also stresses that “Our fight against fascism is political, against their politics and for ours”. – 3WF

|

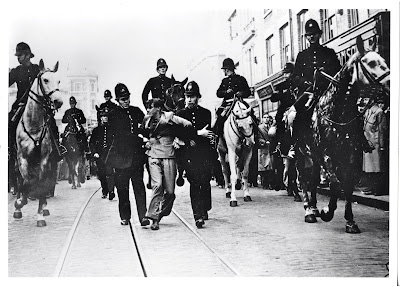

| Battle of Cable Street: antifascists vs fascists vs police |

There Will Always Be More Of Us: Antifascist Organizing

by Paul O’Banion

The events of August 22nd (A22) in Portland, Oregon were a clear victory, with hundreds of people turning out all afternoon on the downtown waterfront to confront the fascists — until it suddenly wasn’t.

The Proud Boys’ last minute change of location — away from the waterfront to a parking lot a half-hour drive away (and even longer on the bus) — resulted in only a relatively small group in bloc engaging in a courageous but ill-considered attempt to confront them: going where they go, but without the necessary preparation and coordination. It turned into, at best, a shit show. Proud Boys smashed up a couple of vehicles, flipping one on its side, beat the shit out of some folks, and engaged in sustained attacks. Our side mobilized a black bloc of roughly thirty; covered Tiny, one of the Far Right’s main instigators, head-to-toe in paint, stopping his club-wielding charge in its tracks; and attacked a photographer. Despite the relative success of the earlier waterfront mobilization, we didn’t end the day looking very good. It’s controversial, but optics matter. The narrative that is created about actions we are involved in is critical to our long-term success.

The events of A22 starkly illustrate the limits of fighting fascists on purely military or tactical grounds. For five years we have battled various fascists, the fascist adjacent, and fascist enabling in the Pacific Northwest, with the most brutal part of the whirlwind being Portland (and not for the first time!). Antifascists have done a remarkable job tirelessly defending against incursions, provocations, and attacks by the Far Right, especially since the 2016 election of Donald Trump. There have been more mobilizations against Patriot Prayer, the Proud Boys, and other knuckleheads than one can remember. Established organizations, such as Rose City Antifa and the Pacific Northwest Antifascist Workers Collective, various crews, affinity groups, and collectives have done exemplary work. Yet, at best, we have achieved a kind of stalemate; at worse, in the larger national and international picture, we are losing.

So how do we start winning? In order to defeat the fascists in a decisive way we need to subsume our tactical struggle to the political one. Contextualizing street fights as one component of a larger effort keeps our focus on our long-term work to build a free, mutualistic, and egalitarian society. We need people on the front lines with skills in martial arts, first aid, and communications. We need people with hacking and doxing skills. And we need to continue developing material support infrastructure and mutual aid efforts for mobilizations. All of this is essential. But A22 showed us that, in-and-of-itself, all this will never be enough.

If we only develop the skills to make us a better fighting force, the fascists will out-maneuver us on the larger terrain and continue to build their movement. To complement our ability to deny the fash the streets and public platforms we need to better contest their attempt to win sympathy for their ideas. This means continuing the longer term, less glamorous work of organizing, talking with other working-class and oppressed people, developing ideas together; in short, creating a broad, popular movement aimed at fundamentally re-making society, getting at the roots of what gives rise to fascism in the first place. We should be able to respond to the questions that the Far Right is answering with our own alternative: a movement and liberatory culture that is so attractive to everyday people that they can’t resist the urge to become involved. Efforts towards establishing ‘everyday antifascism’ as commonplace is one example.

Politics partly involves developing a shared narrative that helps people make sense of the world. This is what the fascists are doing: they are providing stories that help people understand what is going on, providing a sense of meaning and belonging that is both comforting and supports taking action in the world. We too need to keep our focus on the big picture, on winning in the long-term. Our goal should be creating a broad-based popular movement to help create a non-fascist society. By developing our politics together and collectively envisioning what we want and how we think we can best get there, perhaps we will also gain more discipline as a movement — the kind of discipline that allows us not to rush into situations unprepared, disorganized and uncoordinated, to fight the fash on terrain they chose. We need the power and momentum to pick our battles.

What happens in the street is essential. Fascists, on principle, should not be allowed to gather, organize, or speak publicly. But how we do that will determine whether we win the larger war, not just one particular battle. How these confrontations play out to those watching from their workplaces, neighborhoods, bars, and homes is of the utmost importance in determining whether the majority of folks side with us, or support state and fascist violence against us.

The antifascist struggle in Germany is more practically and theoretically advanced, mainly because they’ve been doing it longer. As Bender, an autonomous antifa militant active in Berlin since the 1980s says, “The most important step … [is] to get organized in groups, which would have regular meetings and a clear membership… a common basis of understanding and common goals, and a clear name. These groups would be approachable for others outside the group, and capable of and willing to engage in alliances, they also could take better care of new, interested people. … The groups would also represent their positions publicly in a way that was open to participation.” Bender continues that antifascists should not fight fascists alone, stressing the importance of “temporary alliances with other groups outside the autonomous movement, such as other leftist groups, trade unions, … and so on.” But in collaborating with groups that may not share all of our politics, it is necessary “to maintain our positions and our forms in these alliances. That means to have – at least on a symbolic level – an autonomous standpoint and a radical expression, for example at demonstrations, by using the politics and tactics of the black bloc.

Those in autonomous antifa came to realize that they were becoming marginalized and isolated and that the larger narrative matters, which led them to understanding “the importance of better public relations and being concerned with media representation.” Bender suggests that we can both recognize the role media plays in maintaining the status quo and institutional power, while still engaging it “to produce pictures for the public, which nowadays has become, due to the mechanism of media and politics, part of the ‘society of the spectacle.’” This requires us to be smart about how society works, how people come to form opinions, and how everyday working people come to be willing take risks to fight fascism. It doesn’t mean toning down the level of militancy but better understanding the dynamics of how these confrontations are represented.

An International Struggle

With the dizzying momentum of authoritarian movements around the world and, closer to home, the relentless march of Far Right Trumpist Republicans, we need to understand our struggle as not only local, but national and international. This requires us, as the Far Right is doing, to mobilize and organize a mass, popular movement. In this practical struggle and war of ideas, the fact that being antifascist or believing that Black lives matter are even controversial positions indicate that we are not even close to winning. One of our tasks is to develop antifascism as the “common sense.” If we do this, we can marginalize and limit the growth of fascism, better enabling us to defeat it.

|

| Police clear antifascist’s barricades from the Battle of Cable Streets |

There are plenty of historical examples we can learn from in developing the antifascist movement. We can look at the organizing that brought out hundreds of thousands of people to defend the largely Jewish East End of London against a fascist march in 1936: the famous “Battle of Cable Street.” At that time, members of the Jewish and Irish communities, local workers and Labor and Communist party members, anarchists, antifascists, socialists, and pissed off Londoners all came out to the streets to fight Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists (BUF), and his 3,000 Blackshirts, not to mention the 6,000 police marshaled to protect them. The reason up to 300,000 people mobilized and stood up to Mosley and his fascists on that day is made clear in “The Battle of Cable Street: An Account of Working Class Struggles Against Fascism,” published by the London Trades Union Council SERTUC:

“A common cause of hatred of Fascism brought people together. Charlie Goodman made a name for himself during the battle when he climbed up a lamp post, exhorting people to fight back as they began to waver, and described one alliance: ‘it was not just a question of Jews being there, the most amazing thing was to see a silk-coated Orthodox Jew standing next to an Irish docker with a grappling iron. This was absolutely unbelievable. Because it was not a question of … a punch up between the Jews and the Fascists, it was a question of people who understood what Fascism was.”

We can also look at how “Rock Against Racism” organized, also in England, this time in the late 1970s against the National Front, working with the Anti-Nazi League to turn-out tens of thousands of people in antiracist festivals that made being against fascism part of popular culture, doing so in a fun, engaging, and welcoming way. This is also the approach of today’s Pop Mob (Popular Mobilization) in Portland, Oregon, an organization that has succeeded on several occasions in turning out large numbers of people in part by creating a welcoming and safe place for new and uninitiated folks to come and take a stand. All this complements and backs up front-line fighters and those in bloc, which Pop Mob is explicit about. As Pop Mob spokesperson Effie Baum points out, “without the black bloc, we would not be safe out there because they are the ones who are protecting us from both the violence of the far right as well as the violence from the police, because they are the brave ones who put their bodies between us and those threats. So, the reason that we also have this big tent approach is because we do include that in our diversity of tactics. And I want folks … when they’re out there, they will also see firsthand the truth, which is that they are being protected by people who are engaged in community defense and that it’s not what they’re seeing on TV.”

We can better win our battles with fascists in part by turning out far greater numbers than them. To do this well we need to reach out beyond those already convinced of the need for militant antifascism, going outside our scenes and comfort zones, having difficult conversations, developing politics with a wider group of people than are currently involved.

Examples of what this approach looks like on the ground here in the US is the broad-based antifascist mobilization against the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 that turned out thousands of people; the work in the Bay Area that saw 10,000 folks, including a huge black bloc, show up to confront the “No to Marxism” rally planned in Berkeley later that same month; and in Portland, in August, 2018 when well over a thousand people marched against Patriot Prayer and other fascists behind a well-organized black bloc of several hundred.

Always Be More of Us

The first time I physically confronted Nazis was in Minneapolis in the early 1990s. I was strolling through the streets of Uptown with two comrades I was just getting to know. Our afternoon was suddenly interrupted when a teenager ran up and said, “Hey K-Dog, you used to be a Baldie, right?” K-Dog responded, “I still am a Baldie!” Our young friend excitedly told us he was just hanging out on the train tracks when two older dudes showed him their swastika tattoos and told him to “tell his friends that they are back.” This was just after the Baldies, an antiracist skinhead crew that helped initiate Anti-Racist Action (ARA), had successfully kicked Nazi boneheads out of Minneapolis. K-Dog quickly rounded up a crew of twenty people and we headed to the train tracks. Scouts up ahead spotted the Nazis, shouting back to the rest of us. The Nazis high-tailed it up and off the tracks and back into the streets. We finally surrounded them in a grocery store parking lot; I had a half brick in my hand, and we backed them into the store.

In that moment, with everyday American life swirling all around us, I thought how strange this was: a running battle between us, a motley crew of anarchists, punks, antiracist skins, and disaffected youth versus a couple of scraggly older Nazis. I felt a connection to the historic struggle between antifascism and fascism that has flared up across the last century, mobilizing millions. But here we were, on this warm sunny afternoon, a few dozen of us with crude, improvised weapons in a grocery store parking lot, confronting Nazis while complacent America went about its business. That confrontation between a handful of antifascist militants and a couple of Nazis has now grown far larger. We need to adjust accordingly. The street fights that Anti-Racist Action once engaged in now play out on a national and international level. These fights are no longer only between fascist and antifascist subcultures. They involve all of society.

Our task is to better relate to the larger working-class and other oppressed communities, listen to what they are also going through, develop solidarity, mutual aid, and common understandings, while building power together. We can crush the fascists with numbers, sharing a collectively generated vision of a new society, figuring out how we get there along the way. Our fight against fascism is political, against their politics and for ours. We need to better develop and clarify just what our politics are.

The ongoing discussions and debates amongst antifa, and in sympathetic aligned movements such as anarchism, Indigenous resistance, queer and trans liberation, and the environmental movement, in addition to fora such as this, need to spread amongst our co-workers, neighbors, friends, and family.

During that altercation in Minneapolis, those two disheveled Nazis briefly emerged through the automatic doors of the grocery store to show us their faces and yell, “The only reason you won is cause there’s more of you than us!” To which K-Dog immediately responded, “There’ll always be more of us than you!” And that’s what we should remember: there will always be more of us than them, but only if we out-organize them.

Paul O’Banion is an anarchist organizer. He was active in Minneapolis & New York in the 1990s and is a former member of the Love and Rage Revolutionary Anarchist Federation. O’Banion has organized in Portland for the last two decades, most recently helping found Pop Mob (Popular Mobilization). His Twitter is @Diggers1616

Related posts:

Understanding A22 PDX: discussion and analysis for the antifascist movements

Understanding A22 PDX: Three Responses

Understanding A22 PDX: Never Let the Nazis Have the Story! The Narrative Aspect of Conflict

Understanding A22 PDX: Broader implications for militant movements

It was no Harpers Ferry: August 22d wasn’t an accident, it was a product of our thinking

A Diversity of Tactics is Not Enough: We Need Rules of Engagement