|

| Laying claim to the mantle of Lincoln and FDR. |

Lyndon LaRouche’s recent death at age 96 brought him more attention than he had gotten in decades. Many of the obituaries and retrospectives I’ve seen treat him as little more than a political curiosity, a deranged cult leader whose main achievement was to help inure us to bizarre conspiracy theories, and who lost most of the little influence he had over thirty years ago. But there’s a lot more to him than that.

LaRouche carved out a place on the U.S. far right unlike any other. Few U.S.-based fascist groups maintain strength for more than a few years, but LaRouche kept hundreds of followers in multiple countries tightly organized for over four decades. In the 1980s, his network’s achievements in grassroots electioneering, fundraising, propaganda, and dirty tricks were completely unparalleled on the far right, as Dennis King chronicled in his invaluable 1989 book Lyndon LaRouche and the New American Fascism (available online here). In the late 1980s, the LaRouchites’ practice of systematically defrauding elderly Republicans of millions of dollars destroyed the network’s extensive Reagan administration connections and sent LaRouche to prison for five years. But what’s remarkable is that they were able to rebound from this defeat, remake themselves politically, recruit a new cohort of younger activists, and forge new ties with political elites—this time elites outside the United States. And throughout all of this, LaRouche was able to fly largely below the radar of both the mainstream media and the left, because most people thought he was just a crackpot who claimed the Queen of England pushes drugs.

I was first confronted with the LaRouchites in 1990, during the lead-up to the first U.S.-Iraq war, when one of the founders of my local anti-war group admitted to being a LaRouche supporter. The group voted to expel her (the LaRouchites’ history of spying on and physically attacking leftists overrode people’s desire to be open and inclusive), but then we discovered this wasn’t an isolated incident, but part of a coordinated effort by LaRouche activists around the country to infiltrate the antiwar movement. Trying to make sense of this, of why a fascist organization would be opposing U.S. military expansionism, turning out for leftist-led demonstrations, and accusing George Bush of genocide, was one of the conundrums that led me to start researching far right politics systematically. Since then I have kept tabs regularly on LaRouchite propaganda, partly for its sheer baroque extravagance and partly to mark one of the outer parameters of far right thought in the United States and beyond.

Several commentators have described Lyndon LaRouche as a pioneering conspiracy theorist who helped pave the way for Alex Jones and even Donald Trump. Not so many have delved into the sophisticated utility of LaRouche’s bizarre ideology. His periodic warnings of plots to kill him weren’t just paranoid fantasies but part of the cult psychology he used to control his followers—and extract millions of hours of free labor from them. His seemingly random mix of conspiracist targets—from the Communist Party to the International Monetary Fund, from environmentalists to the Christian right—enabled the LaRouche network to present itself as “conservative” in one situation and “progressive” in another, and to attack or defend people anywhere on the political spectrum with equal facility.

Whether tilting right or left, LaRouche promoted the same basic ideology from the mid 1970s onward. He saw all human history as a massive Manichean struggle between good “humanists” and evil “oligarchs,” a struggle carried out largely behind the scenes. He warned over and over that the world was on the brink of imminent economic collapse, full-scale dictatorship, or nuclear war, and proclaimed himself one of the few people with the insight and will needed to lead humanity out of the crisis. He argued that people could be divided into three levels of “moral development,” and that those at the lowest level were dangerous to society and should not have the same rights as their superiors. Under his 1981 “draft constitution” for Canada, which detailed his vision for how to organize a state, people who espoused “irrationalist hedonism”—basically, any beliefs or practices he considered dangerous, such as homosexuality, laissez faire economics, or rock music—would have no political voice. Yet LaRouche’s drive to reshape society went far beyond political exclusion. Evil oligarchic influence, he declared, must be rooted out of every sphere of society and culture, from economics to mathematical formulas, from technological development to the pitch used to set musical scales.

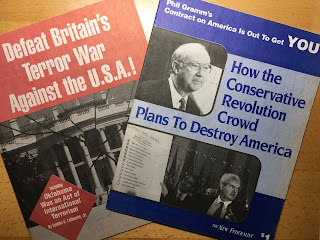

|

| 1990s: LaRouche publications criticize conservatives and blame House of Windsor for Oklahoma City bombing |

Unlike most U.S far rightists, LaRouche was familiar with leftist theory and political culture, having spent over twenty years in the Trotskyist movement and the student left, and he was more effective than most far rightists at delivering his message to people across the political spectrum. He appeared several times on The Alex Jones Show, a right-wing conspiracist radio program with millions of listeners, but his propaganda also repeatedly reached left-leaning audiences, largely with the help of intermediaries such as the Christic Institute, Michel Chossudovsky’s Global Research, and former LaRouche network members William Engdahl and Webster Tarpley, all of whom have given a leftish gloss to LaRouche-originated anti-elite conspiracy theories. As recently as 2016, Helga Zepp-LaRouche (wife of Lyndon and founder of the network’s Schiller Institute) was listed on the program of the Left Forum in New York City. Dennis Speed of LaRouche’s Executive Intelligence Review spoke at the 2015 Left Forum.

LaRouche was also better than most U.S. far rightists at forging ties with people in power. In the late 1970s and early 80s, as Dennis King noted, LaRouche recognized that the post-Watergate crackdown on government abuses made his outfit useful to intelligence agencies interested in outsourcing some of their spying and dirty tricks operations, and that positioning himself as a hawkish Democrat made him interesting to Reagan officials. (In this respect, he may not have looked that different at first glance from the early neoconservatives—some of whom also had a Trotskyist past.)

In the 1990s, LaRouche saw a new opportunity in Russia, where his hatred of international bankers, praise for Vladimir Putin, and advocacy of protectionist, strong-state economic development won him a hearing with many political leaders, including close Putin aide Sergey Glazyev. By the time he died, LaRouche had also made significant inroads in China, where state-run media now quotes LaRouchite journalists extensively and invites them regularly to news conferences. (The LaRouche network’s praise for President Xi Jinping may be opportunistic but it’s also sincere, as Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative represents the kind of large-scale infrastructure project that LaRouche has been advocating for decades.) It’s hard to think of another U.S.-based fascist who has achieved this kind of government access.

Along with shifting the focus of his overtures from U.S. political elites to Russian and Chinese ones, LaRouche shifted his movement’s public stance leftward. In the 1980s the LaRouchites championed Reagan’s Star Wars program and spearheaded ballot initiatives to forcibly quarantine people with AIDS, but in the 1990s and 2000s they were active in campaigns against the U.S.-led wars in Iraq and Yugoslavia and in the Occupy Wall Street movement, glorified Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, and denounced Christian right leaders such as Pat Robertson. The LaRouchites continued to present themselves as New Deal progressives even after embracing Donald Trump’s America First populism.

|

| Presenting LaRouche as ally of African American leaders |

LaRouche’s trajectory set him apart from white nationalists, who put race firmly at the center of their politics. In the 1970s, the LaRouchites vilified black and indigenous people in overtly racist terms, and allied themselves with white supremacists such as Ku Klux Klan leaders Roy Frankhauser and Robert Miles. By the 1990s, however, LaRouche organizations welcomed people of color as members and celebrated civil rights movement veterans—and LaRouche supporters—James Bevel and Amelia Boynton Robinson as heroes. LaRouchites declared African American spiritual music to be “the basis for an American Classical culture”—a worthy counterpart to the European classical culture they constantly celebrated. Sometimes LaRouche reverted to open racism—for example referring to Barack Obama repeatedly as a “monkey”—but the overall effect anticipated the Proud Boys’ racially inclusive “Western chauvinism” much more than the white exclusivism of Richard Spencer or The Daily Stormer.

LaRouche’s antisemitism followed a similar pattern. He began scapegoating Jews in the 1970s at the suggestion of the Liberty Lobby’s Willis Carto, and his conspiracism was deeply rooted in anti-Jewish themes—such as the false dichotomy between “evil” finance capital and “good” industrial capital, and the emphasis on Anglophobia (derived from 19th-century claims that that the Rothschild banking family controlled Britain). But in stark contrast to neonazis, LaRouche included Jews among his supporters and top lieutenants. And over time he became increasingly careful and sophisticated in deflecting the charge of antisemitism, for example by denouncing opponents as “Nazis” and by portraying Jews as tools or dupes rather than as the top wire-pullers.

“From the time of his emergence as a public figure over fifty years ago,” declares his obituary on the LaRouchePAC website, “the only tragedy that characterized Lyndon LaRouche’s life, is that he was never permitted to carry out, either as President or as an adviser to the serving President, the economic reforms that would have improved the lives of tens of millions of Americans and hundreds of millions around the world.” LaRouche never got the power he craved. Despite all his efforts to piggy-back on popular movements, only a limited number of people were willing to submit themselves to his self-proclaimed greatness. Despite his efforts to make himself useful to political elites, his mix of conspiracy thinking, strong-state nationalism, and cultural totalitarianism was ultimately a deal-breaker, at least in his home country. He was profoundly at odds with the neoliberal precepts of privatization, deregulation, free trade, and individualism that have dominated U.S. capitalism for decades.

Still, LaRouche’s impact was real. He not only helped make conspiracism a major part of our political culture, he field-tested a variety of tactics that other rightists could learn from. He was a pioneer of red-brown alliance-building and Russophile “anti-imperialism,” and showed that fascism could be reworked in ways that went far beyond exchanging a brown shirt for a suit and tie. The expectation that his organization will now collapse may or may not prove true. Cults don’t always die with their founders, and his widow Helga Zepp-LaRouche, comparatively young at 70, is a seasoned organizer and speaker who has played an increasingly prominent role in recent years. LaRouche is dead, but unfortunately his politics are not.

Photos by author. Portions of this essay are adapted from Matthew N. Lyons, Insurgent Supremacists: The U.S. Far Right’s Challenge to State and Empire (PM Press and Kersplebedeb Publishing, 2018). See Chapter 5 of that book for additional citations.